|

|

We do not know the precise origins of the Ketuba as the official marriage certificate which also incorporates the obligations of the groom towards his bride. The ketuba is not mentioned anywhere in the Bible. In ancient times, the marriage ceremony was performed in public in the presence of the elders of the congregation and was the occasion for a feast as in the case of Jacob (Genesis 2g.22) and Boaz (Ruth 4.9). The festive, official part of tne ceremony was concluded with the entry of the bride into her husband's tent to begin their conjugal lives as we are told of Isaac and Rebecca (Genesis 24.67). The legal expression for this form of marriage is "marriage through intimacy" as defined in the Rambam's "Yad Ha-Hazaka".

In the course of time the need was felt to provide legal sanction for the marriage act. Jewish life was so bound up with religious responsibilities That "every act performed by a Jew was in accordance with the written or oral law".

In former times, when the woman married, there was no need of a marriage certificate to prove to the community that the couple were living together strictly in accordance with the law, therefore no mention was made in the document of "in accordance with the Law of Moses and Israel" since to those living in the Holy Land, it was self-evident. This wording is to be found for the first time in a ketuba from Alexandria, brought to Hillel, and there it is not part of a religious document but simply is listed as one of the obligations that the woman takes upon herself in her relationship with her husband. However, Gaster is of the opinion that when a woman separates from her husband and remarries while her former husband is still living, there is a need to protect the status and property of the woman and to give this in written form "to protect her against slander and to protect her children's status in the event of her remarrying" i.e. to protect her elementary human rights, her property, etc.

The first specific mention of this type of marriage contract is in the Apocrypha, in the Book of Tobit, and this served as a kind of prototype for the Ketuba "And they inscribed these matters in a book, then they ate, drank and blessed the Lord' (Tobit 7.19). The Mishna attributes the codification of the Ketuba to Rabbi Shimon ben Shetah, Nasi (President) of the Sanhedrin. who lived in the 2nd century B.C.E.

In accordance with Jewish law, the marriage ceremony includes the act of the groom handing his bride the Ketuba whereby he accepts the obligation to supply all her needs in their future life together. The Ketuba serves to defend the woman's position after her marriage and, in the words of the Gemara "so that it will not be easy for him to cast her aside'. The legal importance of the Ketuba in the relations between bride and groom is evidenced by the fact that Jewish law prohibits the husband from spending even one hour with his wife unless she is in possession of the ketuba and should the original certificate be lost, he has to provide her with another. It is interesting to note that the unique status of the Holy Land in Jewish life finds expression even in the law concerning the Ketuba since it is ruled that should the wife refuse to follow her husband to the Holy Land, the Ketuba is automatically annulled.

While the rare and costly Hebrew manuscripts which were written and illuminated by well-known artists before the invention of printing could be commissioned or purchased only by the rich, the Ketuba belongs to the category of those intimate family documents to be found in the possession of every Jewish community at all times. In spite of the injunction that every Jewish woman is to guard her ketuba, very few contracts from previous centuries have come down to us to be preserved in libraries, museums or in private collections,

The Ketubas of Jerusalem, the "Holy Cities" and the Jewish communities of the neighbouring countries (Lebanon and Syria) hold a special place among the ketubas from the lands of Islam, but in spite of the fact that the Jerusalem Ketubas belong, geographically speaking to the Middle [astern group, they are famous for their specific motifs which differ from those employed in the neighbouring Islamic countries.

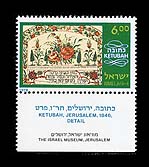

The Ketuba shown on the IL. 6.00 stamp is a typical example of a Ketuba from Jerusalem. It is made of a rectangular parchment at the top of which is a dome crowned by a circle. Around the edges are floral decorations within a double frame (except for the bottom edge). The area within the frame is bisected by pillars supporting a kind of arch. In the upper section are roses flanked on either side by flowers and a pair of cypresses.

The IL. 3.90 stamp portrays an illuminated Ketuba from the Morrocan community of Meknes which clearly shows the influence of Islamic art both in the use of the decorative arabesques and other motifs typical of Arab architecture as well as in the use of blue and green commonly to be found in illuminated Moslem manuscripts.

The Ketuba is a rectangular parchment with a double frame decorated mainly with arabesques in floral and geometric patterns in the margins. The text, in the cursive script used by the Jews of Morocco, is underneath the arch. In the upper corners are two windows at each side, in Moorish style which call to mind the windows of the "El Transito" synagogue at Toledo. On the windows are inscribed the texts "A woman of worth who can find? Her price is above rubies"; "He who has found a wife has found a good thing...'; "May the Lord grant that the woman who enters your house be as Rachel and Lesh"; "May your house be as the house of perez...". The text is written in ink and watercolours (tempera) on paper and coloured in green, blue and ochre.

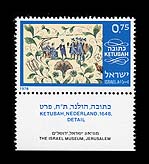

Illustrators of the Ketuba from the Jewish congregations in the Mediterranean area were greatly influenced by Italian art, and they even took this tradition with them when they moved to the Balkan countries or to Holland. In fact, in the 17th century in Holland it was very common to find a ketuba illustrated with highly-coloured floral and figurative motives typical of the Italian-styled Ketuba However, the art of copper etching which made wonderful strides in the Low Countries, also left its mark on the Ketuba and its illumination, since the Jewish artists living in Holland not only knew how to employ the new art, but also excelled in adapting it to serve the needs of the Jewish congregation. The IL. 0.75 stamp portrays one of the most beautiful Dutch Ketubas of the 17th century which have fortunately been preserved for us. We know that the name of its designer - a Jew, Shalom Mordechai taIls, copper-engraver, who reached Holland from Mantua in Italy. The artist made a name for himself as an illustrator of the Book of Esther and a portrayer of leaders of Holland's Jewish community, such as Jacob Judah Leone and Rabbi Manasse ben Israel. In spite of the fact that this ketuba was produced as a copper etching, it illustrates a continuation of the Italian style of illumination by its use of rich artistic motifs, particularly in the use of the delightful coloured, miniatures on biblical themes, each with the appropriate text enhanced by garlands of flowers, At the foot of the ketuba is an escutcheon containing the contract clauses; below this appears the artist's signature "by Shalom Italia".